Photographing the Plains Indians: Ridgway Glover at Forts Laramie and Phil Kearny, 1866

IN The People of the Buffalo:

The Plains Indians of North America. Silent Memorials:

Artifacts as Cultural and Historical Documents

,

by Paula Fleming

vol. 2, Colin F. Taylor and Hugh A. Dempsey (eds.), Tatanka Press 2005

"Did Ridgway Glover take photographs of Fort Phil Kearny?" This is one

of the many intriguing questions that has engaged scholars of the

American West for decades, not the least of which was Dr. John C. Ewers

who regularly inspired me to find an answer to this and many other

questions. It is to his memory that I dedicate this summary of my work

on Glover.

Ridgway Glover (Fig.1) was born into a Quaker family of Mount Ephraim, New Jersey, the son of Elizabeth (Lewis) and John Glover (Fig.2). The first census record to contain specific information on Ridgway is the 1860 New Jersey record for Camden County. 1 He is listed as a 29-year-old farmer with a real estate value of $11,000 and a personal estate of $2,000. If his listed age is correct, he was born in 1831. He lived with Maria Glover, 33, likely his sister, and various farm workers. Clearly they were successful farmers enabling Ridgway to pursue photography as a career.

Nothing is known of why or how he took up photography, but as

Philadelphia was a major photographic center and is a short distance

across the Delaware River, he likely learned the craft by a combination

of contact with local studios and self instruction. He opened a studio

at 818 Arch Street in Philadelphia and in 1864 advertised in the

Philadelphia Photographer 2 as an animal and view photographer.

Fig. 1. Portrait of Ridgway Glover by unidentified photographer. This

modern copy photograph was made in March 1967 in Indianapolis probably

for a relative. Notations on the back not only identify Glover but also

provide brief genealogical and biographical information. This photograph

and others were part of an estate sale in Pendleton, Indiana, now a

suburb of Indianapolis, where Glover had relatives (Author's

collection).

His competitors included Frederick Gutekunst, and proposed future collaborators, Wenderoth and Taylor.

Glover's first photographs of historic importance were stereographs of the Lincoln Funeral (Fig.3) and associated locations. 3 The imprints show that by 1865 he was in partnership with the Schreibers, an important family of Philadelphia photographers. The partnership would break up within a year, perhaps because of either his "wanderlust" or his personality.

According to the Philadelphia Photographer,

He was rather eccentric in

his ways. We have often been amused at his odd-looking wagon as it

passed our office window, and as frequently wondered that he secured as

good results as he did. But he had his own way of thinking, and cared

very little whether any one else agreed with him or not... We shall not

soon forget our first acquaintance with him. A rough, shaggy-looking

fellow entered our office with two foolscap sheets full of writing

hanging in one hand, and with very little ceremony threw them down

before us,remarking that there was an article for the Journal, and walked out. We

promised to examine it; we did so, and next day it was our painful duty

to inform him that his paper was of no use to us. This brought us

another foolscap sheet full of abuse and condemnation of ourselves and

the poor innocent Philadelphia Photographer. We used about six lines in

replying to that, (not yet located) and were again favored with a fourth

sheet crowded with apologies. That was his nature. Impulsive, generous,

and good hearted, to a fault. No one suffered if he could help them"

(Vol.3, Dec. 1866: 371).

According to Father Barry Hagan, Glover struck Col. Henry B. Carrington as a loner and someone who must have suffered some great disappointment in life, but whether this was true or not, we do not know. He did not have a family of his own and clearly the farming life held no appeal. For whatever reason, he decided to take his camera and head West.

Fig. 2. (Left) One-half of a stereo photograph by Glover his family and the house where he was born in Mt. Ephraim New Jersey. Mt. Ephraim is situated across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where Glover worked as a photographer. Other stereo photographs were made by Glover of his family in Pendleton, Indiana, probably during his visit in 1866 prior to his trip West. (Author's collection).

Fig. 3. (Left) Stereo photograph of the Lincoln funeral taken and copyrighted by Ridgway Glover. Of special note is the uneven tones between the two halves and the overall production problems, probably caused by his incomplete mastery of the difficult wet-plate photographic process. (Author's collection).

The late 1860s were a time of great change for the country. The Civil

War was over and the country was changing its focus. The great surveys

of the American West would not begin until the 1870s, but westward

expansion was well underway through Indian territory resulting in both

wars and treaties with the Indians. If a photographer planned to record

the country, especially given the cumbersome photographic equipment and

the foolhardiness of traveling alone, joining an organized group,

preferably a military one, was necessary and that is exactly what

Ridgway decided to do.

On November 27th, 1865, Glover wrote (original spellings maintained]

from his Philadelphia studio to Spencer Baird, the Assistant Secretary

of the Smithsonian Institution,

Dear Friend..... I have been in formed that an expedition through Utah and Teritorys North of Salt Lake City intends to start next April. I am very mutch interested in getting up a set of photographic negatives illustrating the Geology of the U.S. and wish to have an opportunity of traveling through that country and as my means are very limited I would like to go with the expedition if a photographer is needed. I consider myself competent-to give satisfaction in my line of business and if I go can make myself useful I hope in other ways as I am used to taking care of and driving horses....I can fare as roughly and stand as much hardship as most men... Any aid you can give me will I believe be to the forwarding of the object for which The Smithsonian Institute was established.4

He offered references from local photographic professionals such as

Edward L. Wilson, a contributor to the Philadelphia Photographer and

later editor of his own journal, and promised to send samples of his

stereoscopic photographs.

Baird replied on Nov. 30th that he is unaware of any such expedition. By

January of 1866 Glover had sent Baird a sample of his photographs

including one on wood to a Dr. Gill, and added, "Should you have the

opportunity of exerting your influence in my favour, I shall be under

much obligation and endeavour to do my duty to the utmost."5

His return

address was Pendleton, Indiana, where he was staying with relatives on

his mother's side.

Baird thanked Glover for these beautiful specimens,"6 and stated that he was still unaware of any expeditions. Perhaps feeling that a more aggressive approach was needed to further his case, Glover came to Washington, D.C. with letters of reference and visited Baird's superior, Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. Henry redirected Glover to the Office of the Interior but unable to get an interview with the Secretary of the Interior, 69 Glover left his letter of reference with the Chief clerk7. He then returned to Indiana and was impatient to be get on with his plans. He again wrote to Baird, "I do not wish to bore thee any more than I can help but I thought I would keep thee in mind of my expected expedition."8

When they met, Baird mentioned a doctor who was planning to go to Dakota

Territory and Glover acknowledged an interest in accompanying him, or

else a government group. "I will send you pictures as fast as I

can get my negatives back to Philadelphia. Wenderoth Taylor and Brown

No. 914 Chestnut St. will do my printing.9 It is perhaps indicative of a

partnership breakup with Schreiber that he intended to use another

Philadelphia firm to print his negatives. Further he requested a reply

by the end of the month, "if it ain't too much trouble," and if Baird

could not arrange transportation, he should send as many introductions

as possible. Glover ended with a sadly prophetic statement, "I have

turned my face westward and shall not back out untile I get through if

it takes my lifetime."10

At this point things started to move rapidly. On March 15, Baird wrote

to Glover of several opportunities: one in connection with the Pacific

Railroad and another starting on May 1' with a wagon road expedition to

Virginia City. He added, "There is also to be an expedition to Fort

Laramie and the Upper Missouri to treat with the Indians to which you

might be attracted?"11 Baird also wrote to the Secretary of the Interior

stating Glover's desire to accompany an expedition.12 He also asked Glover

to send the testimonials that he had seen during his visit.'Glover

replied that except for the letter he left with the Secretary of the

Interior, the rest were already at the Institution." Baird may have

relocated them, but only one reference letter from a G.W. Fahnestock is

currently in the Smithsonian files.

Glover received Baird's letter just before leaving Pendleton and replied, "beggars should not be choosers,"15 but he would prefer to join the Indian mission, and again stressed that he cared "not on which rout I commence for I anticipate visiting all the most important localitys before I am through."16 The final letter sealing Glover's fate was sent by Joseph Henry on April 30, 1866:

In accordance with your request we made application to the Secretary of

the Interior in your behalf for permission to accompany the

commissioners who are about to proceed to the west for the purpose of

treating with the Indians and with the understanding that you are to

receive subsistence and transportation but no pay, and that a full

series of all your photographic pictures is to be presented to the

Interior Department and another to the Smithsonian Institution.

We are now advised by the Secretary of the Interior, of his assent to

our request, and are informed that if you are still desirous of

accompanying the expedition and will write to the Commissioner of Indian

Affairs, Hon. D. M. Cooley, to that effect, the latter officer will

furnish you with the necessary letter to Mr. Taylor, Superintendent of

Indian Affairs at Omaha, Nebraska to whom it will be necessary that you

report by the 12th of May next. Two parties will be sent out by the

Indian Department, one to proceed by land to Fort Laramie, the other by

water to Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone. It is probable that

you can accompany either party as you may prefer. In view of the

destruction of the gallery of Indian portraits of the Institution by

fire, we would suggest that you lose no opportunity to obtain likenesses

of distinguished chiefs and such representations of Indian life as may

tend to illustrate their manners and customs."18

Fig. 4. One-half of a stereo photograph by Alexander Gardner of Crow delegate at Fort Laramie, 1868. Alexander Gardner not only photographed the various activities but also witnessed the treaty signed by the Crow. Both images of the stereo are in focus and the contrast is good indicating that the wet-plate negative was made and exposed by a skilled professional who could deal with the difficulties of field photography. (Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives #09823800).

Glover quickly responded that he, "will comply with thy request with

regard to the Indians and have no doubt that I will be able to succeed.

I always have in every undertaking so far."19 He then wrote more

completely, of how he was much rejoiced in receiving the news and in

particular that he was glad to learn of Baird's desire of

70 obtaining pictures illustrating Indian life and portraits of

distinguished chiefs. "It is a little out of the line I had marked out

but gratitude commands the first claim. I shall therefore make solars

(an enlargement) so as to enable me to furnish life size portraits for a

set for your museum of oil."20 This was Ridgway's last communication

with the Smithsonian.

On May 15th he arrived in Omaha, Nebraska Territory and registered at the Herndon House. A local newspaper recorded his arrival:

Ridgway Glover Esq., Photographer of the Smithsonian Institute, Washington, arrived in this city last night. He accompanies the Fort Laramie Indian Commission for the purpose of taking solar and stereoscopic pictures of the various Indian chiefs who participate in the Treaty of Fort Laramie ... Mr. Glover is also engaged upon the pictorial staff of Frank Leslie s Illustrated Newspaper and we understand that he proposes to take several views in and about this city, with a view of forwarding them to New York for publication in that widely circulated journal.21

Upon leaving Omaha, Glover's peace-loving world would change dramatically as he left behind the Quaker culture and large Eastern cities he knew for the western expedition he so desired.

The expedition was with one of two Indian peace commissions sent out by the U.S. Government. One headed up the Missouri River to Fort Berthold and Fort Union and the second, which lover selected, to Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory. Regardless of previous treaty agreements, many settlers and gold speculators traveled through this part of Indian territory, disturbing both the Indian's lives, the best of their remaining hunting grounds, and their sacred lands. The government thus decided to negotiate additional treaties with the Oglala and Brule Sioux, and bands of the Arapaho and Northern Cheyenne, to allow travelers safe access through the territory, and to compensate them for the resulting damages and to encourage them towards "civilization" by turning to farming. At the same time, the military was sent to build and secure forts along the Bozeman Trail to protect the settlers whether or not the Indians agreed to the treaties.

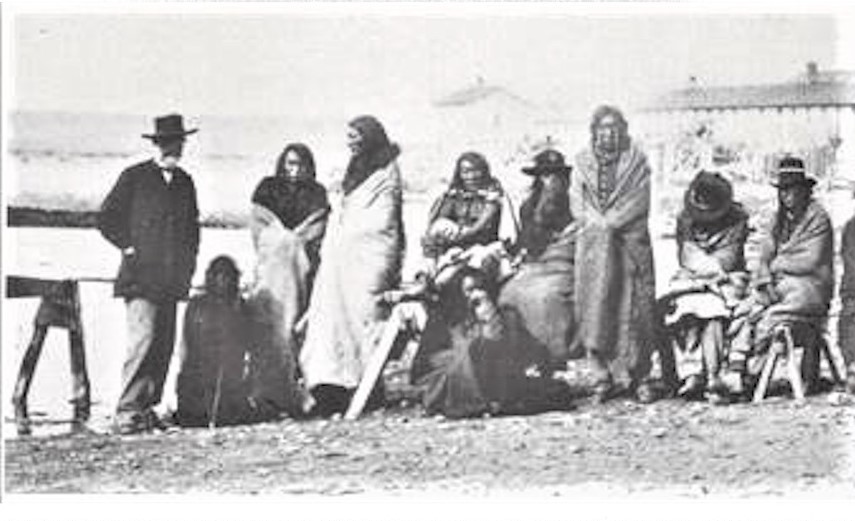

The Fort Laramie Peace Commission consisted of six men: E. B. Taylor, Superintendent of the Northern Superintendency at Omaha, Nebraska Territory and President of the Commission; Frank Lehmer, Assistant Philadelphia; Col. R.N. McLaren, of Minnesota; and Charles E. Bowles, of the Indian Department. Col. Henry Beebe Carrington lead the military troops to Fort Laramie and thence on to establish Fort Phil Kearny on the Powder River.

By early June, the commissioners and several thousand Indians were gathered at Fort Laramie. The arrival of Col. Carrington and the U.S. Eighteenth Infantry on the 13th indicated to Red Cloud and other Oglala leaders, already weary of treaty agreements, that the U.S. government meant to have the land by whatever means necessary, and igniting Red Cloud's war. The establishment of Fort Phil Kearney in Sioux hunting grounds further inflamed the situation.

As the first photo journalist to record treaty negotiations in the field, Ridgway Glover was in the middle of this volatile situation, but by both word and action, he never acknowledged or perhaps understood that he was in danger.

His first letter to the Philadelphia Photographer on June 30th, written during the treaty negotiations, indicates he was photographing the various activities. "I have been in this wild region nearly a month, taking scenes in connection with the Treaty that has just been made with the Sioux, Arapahoes and Cheyennes, and have secured twenty-two good negatives ... that will illustrate the life and character of the wild men of the prairie.... They will come in with the Commissioners. They return on the 2nd of July" (Glover, Aug. 1866: 239).

Fig. 5. One-half of a stereo pair showing Gray Eyes camp at Fort Laramie. This nicely composed and well executed group portrait is credited to Alexander Gardner and shows his ability to capture both formal and informal scenes. (Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives #09824600).

Fig. 6. One-half of a stereo pair showing a Crow woman cooking at Ft. Laramie. A comparison of this image and Fig. 5 shows a vastly different quality of negative. Given that Glover writes about problems he encountered making photographs in the field and the earlier technical problems of his Lincoln photographs, it is possible this image was made by him instead of Gardner. A copy of this and other scenes of lesser quality depicting ponies, which Glover also mentions, appear in the Blackmore collection along with the original of Fig. 8. (Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives #01601909).

The complex photographic process of applying collodion to the glass plates, sensitizing and exposing them while still sticky, and then developing them was a challenge. The water was muddy, hard and full of sand due to the rapid currents and out of the fifty negatives he exposed, more than half were unusable. This is critical as he was using up precious supplies. The frontier photographer had to carry everything except water. If anything happened to either equipment or supplies, activities ceased until they could be repaired or replaced. Even in Omaha there were, "but few people [who] know much about the art" (ibid.), and the further he went into the wilderness, the more difficult it would be to restock. He would have to rely on the military to bring chemicals, etc., and they would be loathe to take up precious cargo space from much needed medical and other supplies

Technical problems were not the only obstacles Glover encountered: "I had much difficulty in making pictures of the Indians at first, but now I am able to talk to them, yet I get pretty much all I want... I have succeeded very well with Indian ponies as you will see... Some of the Sioux think photography is "pazutta zupa' (bad medicine)" (ibid.). Further, "Some of the Indians think they will die in three days, if they get their pictures taken.... I pointed the instrument at one of that opinion. The poor fellow fell on the sand, and rolled himself in his blanket. The most of them know better though, and some I have made understand that the light comes from the sun, strikes them, and then goes into the machine. I explained it to one yesterday, by means of his looking-glass, and showed him an image on the ground glass. When he caught the idea, he brightened up, and was willing to stand for me" (ibid: 239-240). He also mentions making ferrotypes, ("tintypes") for the Indians. As he could not print his negatives in the field, this would have been the only process available to him for giving the Indians positive images, but his diplomacy also meant he was using up more valuable supplies. Perhaps some of these tintypes have survived, but none have been identified and likely given their exposure to the elements, unlikely.

On the 30th of June, he photographed some of the treaty activities and

further reactions of the Indians.

To-day I was over trying to take the 'Waheopomony' (probably a give away

ceremony] at the great Brulie Sioux village. The wind blew so hard I

could not make but one passable negative, though I had some of the most

interesting scenes imaginable. Here the division of the presents from

the Government, was made and some 1200 Sioux were arranged, squatting

around the Commissioners in a large circle, three rows deep. The village

embraces more than 200 tribes (lodges) led by "Spotted Tail,''Standing

Elk," "The Man that walks under the ground,' and 'Running Bear.' 'The

Man that walks under the ground is a good friend of mine. He and the

'Running Bear' have had their pictures taken. I have been introduced to

the other two, and they are friendly. So I took all I chose, or rather

all I could (ibid.).

He also hinted at the dangers of being a frontier photographer. "There was a Mr. and Mrs. Laramie 22 who used to take a mean style of ambrotypes here, but he died, and she was captured by the Indians, and after suffering many hardships, escaped and returned to the States" (ibid.).

Glover expounds on the scenery and wildlife, and goes into detail about

images he took on July 2nd at the end of the negotiations which may

provide us with clues to identify existing Glover photographs. He

photographed the fort from across the Laramie River, and had the good

fortune, "to be present when Colonels McLean and Thomas Wistar were

distributing the goods to the Chiefs, and although the interpreters were

discouraged, and the Indians seemed unwilling, Thomas and McLean at last

persuaded them to sit, and I got a stereoscopic group of six Ogholalla,

and eight Brulie Sioux. The wind was

blowing, and the sand flying. The negative is, therefore, not quite

clean, but all the likenesses are good, and they can be readily

recognized.

They are, BRULIES,

'Spotted Tail,' 'Swift Bear, 'Dog Hawk,' *Thunder Hawk, 'Standing Elk, Tall Mandan, "Brave Hear, White Tail.

OGHALOLLAHS (They pronounce it), *The Man that walks under the ground,'

'The Black War Bonnet, 'Standing Cloud,' Blue Horse,' "Big Mouth,

"Big Head.

The Signers of the Treaty."

His listing has been reproduced exactly as it may indicate the arrangement of individuals in a group and thus help to identify a missing Glover image. Of importance in this group is "Standing Elk" which will be discussed later. The two images of the fort and the treaty signers brings the total of known, good Glover negatives to twenty-four. As he made no further reference to the negatives, we must assume they were given to the Commissioners as planned. Glover then started the next phase of his trip - the journey to Fort Phil Kearney. He left Fort Laramie on July 18 with one of Carrington's wagon trains under the command of Lieut. Templeton. The party consists of six other officers, the post chaplain, a Mr. White, ten privates, "nine drivers, three women and five children and Glover" (Glover, July 1866: 339). The first seventy miles or so there was little scenery worth photographing until he makes a stereoscopic view of the Platte River above Buyer's Ferry.

Glover's first impressions of the Indians were made during the treaty negotiations, "I there saw the lazy, sleepy red man treating for peace and friendship" but that view would change. After three more days travel they reached Fort Reno and about July 22 reached Crazy Woman's Fork of the Powder River. "[The Indian] has since appeared to me as the active, wide-awake savage in the war-path, and made me think of two lines of an old song: 'They you have Indian allies-you styled them by that name-Until they turned the tomahawk, and savages became(ibid.). The party was surprised by Indians at the fork. Lt. Templeton returned to the group ahead of a string of Indians and Lt. Daniels was killed. "Our men with their rifles held the Indians at bay until we reached a better 73 position on a hill, where we kept them off until night, when Capt. Burroughs...coming up with a train, caused the red-skins to retreat. They looked very wild and savagelike while galloping around us." Instead of defending the party, Glover reacts as a photographer." I desired to make some instantaneous views, but our commander ordered me not to" (ibid.). Burroughs led them back to Fort Reno where they restocked and joined two other trains before heading out again. This time they were not attacked and Glover made a photograph of the battle ground. Twenty miles beyond they stopped at Clear Creek where they again encountered Indians." Cheyennes came into camp; but my collodion was too hot, and my bath too full of alcohol, to get any pictures of them, though I tried hard. They attacked our train in the rear, killed two of the privates, and lost two of their number" (ibid.). The next day, ca. July 24, they finally reached Fort Phil Kearney. "I am surrounded by beautiful scenery, and hemmed in by yelling savages, who are surprising and killing some one every day. I expect to get some good pictures here..." (ibid.)

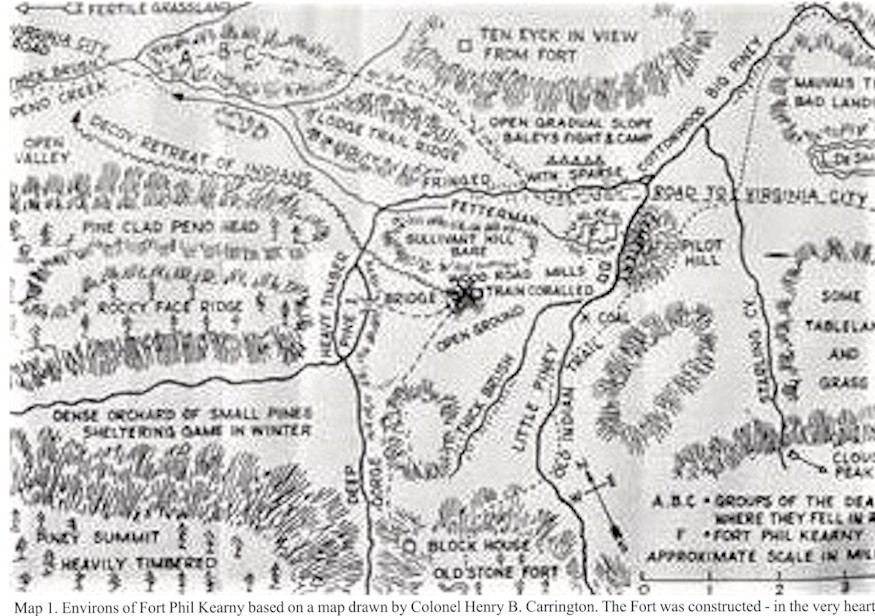

Glover's third and last letter to the Philadelphia Photographer, dated August 29, was not published until the December issue. He was then living in the Pineries with the detail of wood choppers six miles from the fort at the foot of the Big Horn Mountains (Map 1). Although he had hoped to send more information on his photographic activities, that was not to prove the case. "Here I have been waiting for the medical supply train to come up, to get some chemicals, being at present in a 'stick;' but, though unable to make negatives, I have been enjoying the climate and scenery, both being delightful" (Glover, Dec. 1866: 367). Not only had he run out of supplies, but he broke the ground glass of his camera and had to make a new one using charcoal from soft wood to polish the glass.

He spent much of his time hiking alone for days in the mountains, sometimes traveling as much as fifty miles and again apparently unconcerned for his safety. The most dangerous situation was an encounter with a grizzly bear. "I was about firing a ball into his rump, but, fortunately, thought what he was in time; had I fired, you would have received no more letters from me" (ibid: 369). He expected to remain there for the winter, but unfortunately his luck ran out.

The same issue of the Philadelphia Photographer carried the following:

Obituary. Our apprehensions concerning our Indian correspondent, Mr. Ridgway Glover, have proven to be true. On the 14th of September, he left Fort Philip Kearney, with a private as a companion, for the purpose of making some views. It was known that the hostile Sioux were lurking around, but, knowing no fear, and being ardent in the pursuit of his beloved profession, he risked everything, and alas! The result was that he was scalped, killed, and horribly mutilated. The study of the red man was a favorite one with him, and he asserted his belief that they would not hurt him (ibid: 371).

A friend of Glover's and the Post Chaplain both wrote letters to Frank Leslie s Illustrated Newspaper concerning the death of their photographic journalist. Several accounts have been written and they vary greatly in detail. David White, the Chaplain who traveled with Glover to the fort writes, "...he was coming from a cabin, some six miles from this place, by himself, when he was killed by Arapahoe Indians (supposed to be) and scalped. His body was recovered and brought in, and will be buried in the Post burying-ground.23 He was shot with a ball and instantly killed, the ball passing near his heart. I mention this fact that his friends may be relieved of the horrors of savage torture. I do not know his address, and so the publication of this seems the more necessary for the information of any relative or near friends" (Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1866: 94).

His friend, Samuel Peters, told a different story: "He was out sketching for you-his long absence occasioned no little anxiety-and a party went out (members of the 18th Infantry), and found his body. The head was found a few yards off, completely severed from the trunk, scalped. The body was disemboweled, and then fire placed in the cavity. His remains, horribly mutilated, were decently interred, and search made for his apparatus, but it could not be found" (ibid.).

F.M. Fessenden, a musician with the Eighteenth U.S. Infantry Band at the Fort provided additional information. He believed that Glover had a camera outfit with him and was taking views for Leslies at the time of his death. Fessenden had often joked with Glover about his long yellow hair [although it does not appear very blonde in his portrait and that the Indians would delight in clipping it for him, but Glover remained firm in his belief that they would think he was Mormon and therefore safe. Fessenden's wrote that his prediction proved correct. When he and two other men found the body, "...they had clipped that long hair, taking the entire scalp. He was lying on his face, and his back was slit the entire length. Several arrows were sticking in the body" (Hebard and Brininstool 1922, 2: 96).

The authenticity and reasons for variations in the reports on Glover's death and the subsequent treatment of the body would be interesting points of discussion. Even the date of his death varies from September 14 to the 17th (Sunday, September 16 is correct), but for the purposes of ascertaining if Glover made photographs at the Fort, I will focus on the photographic aspects.

The crux of the problem depends upon whether he was able to restock his supplies and if his camera was functional. A medical supply train did eventually get through, but whether he received photographic chemicals before he died is still a matter of speculation.

The Philadelphia Photographer claims he was out making views; Fessenden believed he had a camera and clearly did not have. Thus I do not think that Glover photographed Fort Phil Kearney.

It is possible, however, that he did have part of his camera with him and may have used it as a camera obscura whereby the image was focused on paper and traced rather than recorded on a sensitive emulsion. In affect, the same technique he used to demonstrate photography to the Indians at the treaty negotiations. Additionally, photographic supplies would not be needed. This might explain why he found it necessary to make another ground glass when his broke and further it would explain why his affects did not include a complete photographic outfit.

Although Fessenden states that no equipment was found, they may not have

had sufficient time to make a safe and complete search or perhaps it had

been destroyed and the pieces dispersed. Unless the unlikely event

occurs that Glover photographs are located with the proper provenance

and identification, this aspect of Glover's photographic activities must

remain a mystery.

The fate of his Fort Laramie negatives, however, may yet be solved.

According to Glover, the Peace Commissioners were to bring the negatives

back with them and then forward them to Philadelphia for printing

Certainly the Commissioners returned with their reports. Of the six who

attended the negotiations, the three most likely to have returned to

Washington, D.C. along with their escort were Edward B. Taylor, the

President of the Commission, who probably presented his report in

person; Charles E. Bowles of the Indian Department, and Thomas Wistar,

the Quaker from Philadelphia.

Assuming that the negatives made it to the East intact, two possibilities can be suggested as their most likely fate. The first is that they made it to Philadelphia. Photo Historian Robert Taft states that the negatives reached Wendroth, Taylor and Brown in Philadelphia and were printed although his source is not noted (Taft 1938: 276). As important as these photographs would be to the curious photo-buying public, especially after the Fetterman Massacre, if negatives were available they would have been popular and copies would have survived, but to date no image under the Wendroth imprint has been located.

If the negatives actually made it to Philadelphia, and Wistar returned home, he would have been the most likely candidate to have transported them. In-depth searches of

Fig. 7. The 1866 Peace Commission (I. to r.): Col. R.N. Maclaren, Col. Henry E. Maynadier, Thomas Wistar, Charles E. Bowls and Col. E.B. Taylor, probably photographed by Ridgway Glover. As the Commission members did not travel together, this image had to have been taken out West while Glover was with them. The image mount carries the imprint of D. Hinkle of Germantown, a suburb of Philadelphia, where Glover's negatives were to be transported for printing. The curved upper margin of the print indicates that this was originally half of a stereo pair, a fornat favored by Glover. (Larry Ness collection).

Philadelphia repositories have not uncovered them, but the possibility exits that the negatives are associated with Wistar's papers, if they still exist.

A second, and perhaps more likely explanation of the fate of the

negatives is that they made it no further then Washington, D.C.24 In

1868, the U.S. Government again held treaty negotiations at Fort Laramie

and Alexander Gardner, the important Civil War photographer, accompanied

the Peace Commission and photographed the events. Gardner was an

experienced, master photographer. He, too, had to contend with the

difficult regional photographic conditions that Glover encountered, but

nonetheless, he knew how to frame and focus shots. Yet when one compares

the photographs that are circulated, varying levels of skills can easily

be detected. Many of these views are sub-standard to those Gardner

normally produced in the field (Fig.4, 5, 6). There are also general

camp scenes not tied to specific individuals or events, such as shots of

Indian ponies, and further they match some of the scenes described by

Glover.

It is my belief that at least some of Glover's negatives got only as far

as Washington, D.C. and that Gardner printed them later. It is important

to note that Gardner himself does not take credit for these views, they

are merely on the same mounts. Earlier in his career when he worked for

Mathew Brady, it was Gardner's position that photographers themselves

should get credit for their work instead of the studios that employed

them. While Gardner may have had problems in the field which caused

differences in quality, given his level of professional skills it is

more likely that he fulfilled the Government's plan to print the Glover

negatives, and used the images to round visual impressions of treaty

negotiations in the field.

A few glass-plate negatives of Fort Laramie exist in the Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives in both the wet and dry plate formats. The dry plates

are copy negatives, but many, if not all of the wet-plates also appear to be copies. The images on these plates are from the series Gardner took. If original glass plates could be found of both the Gardner images and those that potentially were made by Glover, chemical analysis could solve the problem. Each photographer had their own collodion "recipe" which was chemically unique. Fingerprints, too, are common in the once-sticky emulsions and while names could not be attached to specific prints, they could be compared.

There is other evidence that at least some of Glover's negatives did survive the return trip. The first image to support this is a carte de visite of the 1866 Peace Commissioners (Fig. 7). The entire Commission is present and identified, and posed in front of a wooden building. The image carries the imprint of "D. Hinkle, Germantown." Germantown is a suburb of Philadelphia that was settled by Quakers and Mennonites. Clearly the commission did not sit for their portrait in Pennsylvania, and thus the image had to have been made during the time they were convened. The only available photographer was Glover. Further the print itself appears to be half of a stereographic pair with its curved upper edge and we know that Glover favored that format. Thus it is very likely that this group portrait was taken by Glover and proof that at least one of his negatives made it to the East.

Fig. 8. Half of an uncredited stereo portrait of Standing Elk. The

rather fuzzy image was collected by William Henry Blackmore, who knew

both Alexander Gardner and Gen. Carrington. His cryptic note for this

photograph reads, "Dahcotahs Fort Phil Kearney Massacre - Standing Elk [illeg.)

Gen. Carrington." Glover specifically mentions taking a photograph of

Standing Elk on July 2, 1866. Given the quality of the image and the

possibility that Glover's negatives were acquired by Gardner, it is

possible that this is one of the lost Glover photographs. (British

Museum Am/B33/1). Further research after this paper was written

indicates that this image was taken after Glover died and thus can not

be credited to him.

There is a second image that is also likely to have been taken by

Glover. There exists in the British Museum a poor quality stereo

photograph of Standing Elk (Fig. 8). This was collected by William Henry

Blackmore, an Englishman with a deep interest in Native Americans.

Blackmore traveled around the United States contracting photographers

and collecting images of the Indians. Most of the originals went to his

museum in Salisbury, England, and eventually transferred to the British

Museum.

Of importance is a note Blackmore attached to this image, "Dahcotah's. Fort Phil Kearney Massacre. Standing Elk (illeg.) Carrington." Given the subject, the quality, and the fact that Glover stated that he had photographed Standing Elk, there is a good potential that Glover took this image. How then, did Blackmore come by it? He may have obtained it directly from Gardner as they were in contact. Further, the images Gardner takes and provides to Blackmore carry his own credit line while this portrait is uncredited. Alternatively, Blackmore could have acquired the image directly from Carrington when he visited him at Fort Sedgwick, Colorado in September of 1868 or in 1875 when Carrington visited him in England (Taylor 1980: 43-44). To date, these two portraits are the most likely images to have been taken by Glover at Fort Laramie in 1866, but there is hope that more have survived.

76 In the mid 1990s, a small photographic auction in Canada listed a

group of photographs taken by Ridgway Glover. The lot consisted of

stereographs Glover had taken of his family, both in Camden, New Jersey

and Pendleton, Indiana, in 1865 (Fig. 2). Included in the lot was a

portrait of Glover (Fig. 1). That portrait was a modern photographic

copy made by an Indianapolis department store in 1967. Pendleton,

Indiana, where Glover's relatives lived, is outside Indianapolis. The

stereos had both vintage and modern notations delineating the

relationships of the people to Ridgway. This was clearly the collection

of a relative and not an historian) who was interested in family

history.

The auction lot had been acquired from an antiques dealer and were the

remains of an estate. Other photographs had been sold during initial

estate yard sales, but what they depicted is unknown. Genealogical

searches via the web have since provided contacts with some of Glover's

descendants, and family photographs credited to Glover are being

uncovered. Although none to date are of Native Americans, they are

providing useful images and additional clues.

While a major cache of Glover's photographs has not been located, positive leads and fruitful new areas to search are opening up. Given the rising value of vintage photographs and wide accessibility of data online, it is probably only a matter of time before the missing Glover images are found, or the story of their demise is uncovered. The scholarly hunt continues.

Map 1. Environs of Fort Phil Kearny based on a map drawn by Colonel

Henry B. Carrington. The Fort was constructed in the very heart of

Lakota country - in the summer of 1866. Ridgway Glover had accompanied

Carrington's force and in August 1866 he was staying with wood choppers

in the Pineries some six miles west of the Fort. It was from here that

he explored the area. Tragically, in September 1866 he was killed by

Arapaho (?) Indians about two miles from the fort. The exact location of

his death is unknown but the author speculates that it was near the

Sullivant Hill (x on the map). It is possible that Glover is still

buried in this region (see Addenda). (From a map drawn by John N.

Turner).

Addenda

As this manuscript was going to press, another series of events

in the search for Ridgway Glover occurred. In carly 2004 a major

American oil company that owns large tracts of land in Wyoming,

including the location of Ft. Phil Kearny, decided to sell their land,

potentially opening it up for development and destruction of the Fort.

Public outcry and sympathetic state officials have come to the defense

of the Fort and are currently working with the oil company to find ways

to protect the site. Curiously, Glover has become the focus of this

protection initiative not only because of his compelling story but also

because it appears likely that his remains were not transferred to the

Little Big Horn

In 1881, Lt. Commander Jasper [?] Byron was in charge of moving graves

from Fort Phil Kearny to the Little Big Horn. In his report he noted,

"If there is any record showing who were buried in the numbered coffins

I would like to have it. Outside of the trench there are 28 graves. By

the best information I can get there are 15 citizens and 15 soldiers

buried in these separate graves." According to records at the Little Big

Horn, only four anonymous civilians were transferred to their cemetery,

two of which are 77

believed to have died in the Fetterman Battle. Given the nature of

Glover's death, it is likely that he could have been identified.

These facts have led the Fort Phil Kearny preservationists to search for

graves still remaining at the Fort. Using aerial photographs and known

coordinates for the cemetery, they have tentatively identified three

graves and there are strong rumors of a second cemetery. These remaining

graves would account for the balance of the civilians not transferred to

the Little Big Horn.

In 1962 and again in 1984, the oil company ran lines through the

property and might casily have disturbed some of the graves; however, it

is hoped that a proper survey will be made of the region to identify

what graves might still exist. While there is no way of knowing if

Glover is still there, unless these graves are located, exhumed and DNA

tests performed. The oil company is fortunately working with the state

of Wyoming to come to a mutually agreeable solution for preserving the

Fort, and Glover descendants are willing to help identify their ancestor

if need be.

For further details see the following which contain the articles by

James Headley in The Buffalo Bulletin for: